Two communes… two life styles… and the same quest for Utopia. Wheeler Ranch: free land—live-in, drop-in.—Commune DirectoryTHE FRONT WHEELS DROP and the car thuds down a wet, muddy ravine. Thick night fog, raining hard. The car squishes to a stop, front end buried in clay and the right rear wheel spinning. I get out and sink to my ankles. No flashlight. No waterproof gear. Utter blackness, except for the car’s dulled lights under the dirt. I climb back in, but because of the 45-degree angle, I’m pitched forward against the dashboard. Turn on the radio. Only eight o’clock —a long wait until daylight. Am I anywhere near Wheeler Ranch? Haven’t seen another car or a light anywhere on this road.

I start honking the horn. Cows bellow back from what seems very close range. I imagine angry ranchers with shotguns. Tomorrow is Sunday—eight miles back to the nearest town, and nothing will be open.

Is there an AAA out here? Good God, I’ll pay anybody anything! If they’ll just get me out of this.

I had started north from San Francisco in late afternoon, having heard vague descriptions of a commune called Wheeler’s that was much beloved by those who had passed through it. The commune had had trouble with local police, and no one was sure whether the buildings were still standing or who was there. At sunset, a storm came up, and rather than turn back, I continued slowly along narrow, unlit country roads, my headlights occasionally picking up messages like “Stop War,” painted on the side of a barn, and “Drive slowly, no M.D. Around,” on a fence post.

When I reached the woodsy, frontier town I knew to be near Wheeler’s, I stopped in a bar to ask directions. Heads turned. People froze, glasses in hand. A woman with an expressionless, milky face said, “Honey, there isn’t any sign. You just go up the road six miles and there’s a gate on the left. Then you have to drive a ways to git to it. From where I live, you can see their shacks and what have you. But you can’t see anything from the road.”

After six miles, there was a gate and a sign, “Beware of cattle.” I opened it and drove down to a fork, picked the left road, went around in a circle and came back to the fork, took the right and bumped against two logs in the road. I got out and moved them. Nothing could stop me now. Another fork. To the left the road was impassable—deep ruts and rocks; to the right, a barbed-wire fence. Raining harder, darker. This is enough. Get out of here fast. Try to turn the car around, struggling to see… then the sickening dip.

I got into my sleeping bag and tried to find a comfortable position in the crazily tilted car. My mood swung between panic and forced calm. At about 5:00 a.m., I heard rustling noises, and could make out the silhouettes of six horses which walked around the car, snorting. An hour later, the rain let up, and a few feet from the car I found a crude sign with an arrow, “Wheeler’s.” I walked a mile, then another mile, through rolling green hills, thinking, “If I can just get out of here.” At last, around a bend were two tents and a sign, “Welcome, God, love.” The first tent had a light burning inside, and turned out to be a greenhouse filled with boxes of seedlings. At the second tent, I pushed open the door and bells tinkled. Someone with streaked brown hair was curled in a real bed On two mattresses. There was linoleum on the floor, a small stove, a table, and books and clothes neatly arranged on shelves. The young man lifted his head and smiled. “Come in.”

I was covered with mud, my hair was wild and my eyes red and twitching. “I tried to drive in last night, my car went down a ravine and got stuck in the mud, and I’ve been sleeping in it all night.”

“Far out,” he said.

“I was terrified.”

The young man, who had gray eyes set close together and one gold earring, said, “Of what?”

“There were horses.”

He laughed. “Far out. One of the horses walked into Nancy’s house and made a hole in the floor. Now she just sweeps her dirt and garbage down the hole.”

My throat was burning. “Could we make some coffee?”

He looked at me sideways. “I don’t have any.”

He handed me a clump of green weeds. “Here’s some yerba buena. You can make tea.”

I stared at the weeds.

“What’s your name?” I asked.

“Shoshone.”

“Mine’s Sara.”

“Far out.”

He got dressed, watered the plants in the greenhouse, and started down a path into the bushes, motioning for me to follow. Every few feet, he would stop to pick yerba buena, listen to birds, watch a trio of pheasants take off, and admire trees that were recently planted—almond, Elberta peach, cherry, plum. They were all in blossom, but I was in no mood to appreciate them. After every ten minutes of walking, we would come to a clearing with a tent or wooden shack, wake up the people in their soggy sleeping bags and ask them to help push the car out.

The dwellings at Wheeler’s are straight out of Dogpatch—old boards nailed unevenly together, odd pieces of plastic strung across poles to make wobbly igloos, with round stovepipes poking out the side. Most have dirt floors, though the-better ones have wood. In one tent, we found a young man who had shaved his head except for one stripe of hair down the center, like a Mohican. He grinned with his eyes closed. “In an hour or so, I might feel like helping you.”

We came to a crooked green shack with a peace sign on the door and the inside papered with paintings of Krishna. Nancy, a blond former social worker, was sleeping on the floor with her children, Gregory, eight, and Michelle, nine. Both have blond hair of the same length and it is impossible to tell at first which is the girl and which the boy. At communities like this, it is common for children to ask each other when they meet, “What are you?”

Nancy said, “Don’t waste your energy trying to push the car. Get Bill Wheeler to pull you out with his jeep. What’s your hurry now? Sunday’s the best day here. You’ve got to stay for the steam bath and the feast. There’ll be lots of visitors.” She yawned. “Lots of food, lots of dope. It never rains for the feast.”

Shoshone and I walked back to the main road that cuts across the 320-acre ranch. The sun had burned through the fog, highlighting streaks of yellow wild flowers in the fields. Black Angus cows were grazing by the road. People in hillbilly clothes, with funny hats and sashes, were coming out of the bushes carrying musical instruments and sacks of rice and beans. About a mile from the front gate we came to the community garden, with a scarecrow made of rusty metal in the shape of a nude girl. Two children were chasing each other from row to row, shrieking with laughter, as their mother picked cabbage. A sign read, “Permit not required to settle here.”

BILL WHEELER WAS WORKING in his Studio, an airy, wood-and-glass building with large skylights, set on a hill. When Bill bought the ranch in 1963, looking for a place to paint and live quietly, he built the studio for his family. Four years later, when he opened the land to anyone who wanted to settle there, the county condemned his studio as living quarters because it lacked the required amount of concrete under one side. Bill moved into a tent and used the studio for his painting and for community meetings.

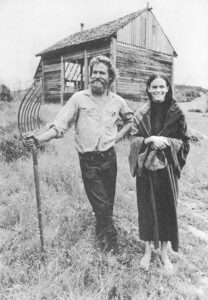

Bill is a tall, lean man of thirty with an aristocratic forehead, straight nose, deep-set blue eyes, and a full beard and flowing hair streaked yellow by the sun. His voice is gentle with a constant hint of mirth, yet it projects, like his clear gaze, a strength, which is understood in this community as divine grace. Quiet, unhurried, he progresses with steady confidence toward a goal or solution of a problem. He is also a voluptuary who takes Rabelaisian delight in the community’s lack of sexual inhibitions and in the sight of young girls walking nude through the grass. He lives at the center of the ranch with his third wife, Gay, twenty-two, arid their infant daughter, Raspberry. His humor and self-assurance make it easy for those around him to submit to the hippie credo that “God will provide,” because they know that what God does not, Bill Wheeler will.

Bill promises to rescue my car after he has chopped wood and started a fire for the steam bath. “Don’t worry,” a friend says, patting me on the back. “Bill’s saved people who’ve given up hope, lost all confidence.” A grizzly blond called Damian says, “Why don’t you let me pull her out?” Bill says. “Damian, I love you, but I wouldn’t trust you with any of my vehicles.” Later, we pass Damian on the road, into which he is blissfully urinating. “Ha,” Bill says, “the first time I met Damian he was peeing.”

With the jeep and a chain, Bill pulls out the car in less than two minutes, and as it slides back onto secure road, I feel my tension drain away. Maybe I should stay for the feast. Maybe it really is beautiful here. I park the car at the county road, outside the first gate, and walk the three miles back to Wheeler’s. The access road cuts across property owned by James G. Kelly, a breeder of show cattle and horses, who is enraged at the presence of up to a hundred itinerant hippies on the ranch adjacent to his. He has started court action to block Wheeler from using the access road, and his hired hands walk around with guns slung over their shoulders and their faces pinched with bilious hate.

On a bluff behind Wheeler’s garden, the steam bath is set to go. Red-hot rocks are taken from the fire into a plastic tent that can be sealed on all sides. Shifts of eight or nine people undress and sit on the mud floor, letting out whoops, chanting and singing. Gallon wine jugs filled with water are poured on the rocks, and the tent fills up with steam so hot and thick that the children start coughing and no one can see anyone else. After a few minutes, they step out, covered with sweat, and wash off in a cold shower. The women shampoo their hair and soap up the children. The men dig out ticks from under the skin. Much gaiety and good-natured ogling, and then, as the last shift is coming out, a teen-age visitor carrying the underground Berkeley Tribe wanders in and stops, dumbfounded, staring with holy-fool eyes, his mouth open and drooling, at all that flesh and hair and sweat.

The garden, like a jigsaw puzzle whose pieces have floated together, presents the image of a nineteenth century tableau: women in long skirts and shawls, men in lace-up boots, coveralls, and patched jeans tied with pieces of rope, sitting on the grass playing banjos, guitars, lyres, wood flutes, dulcimers, and an accordion. In a field to the right are the community animals—chickens, cows, goats, donkeys, and horses. As far as the eye’ can see, there are no houses, no traffic, nothing but verdant hills, a stream, and the ocean with whitecaps rising in the distance. Nine-year-old Michelle is prancing about in a pink shawl and a floppy hat warbling, “It’s time for the feast!” Nancy says, “The pickin’s are sort of spare, because tomorrow is welfare day and everybody’s broke.” She carries from the outdoor wood stove pots of brown rice—plain, she says, “for the purists who are on Georges Ohsawa’s ten-day brown-rice diet”—and rice with fruit and nuts for everyone else; beans, red and white; oranges and apples: yogurt; hash; pot; acid; mescaline. A girl says there are worms in the green apples. Another, with a studious voice and glasses, says, “That’s cool, it means they were organically grown. I’d rather eat a worm than a chemical any day.” They eat with their fingers from paper plates, and when the plates are gone, directly from the pot. A man in his forties with red-spotted cheeks asks me if I have any pills. “I’ll take anything. I’m on acid now.” I offer him aspirin. He swallows eight.

Everyone who lives at Wheeler ranch is a vegetarian. By some strange inversion, they feel that by eating meat they are hastening their own death. Vegetarianism is, ironically, the aspect of their lifestyle that aggravates even the most liberal parents. (“What? You won’t eat meat? That’s ridiculous!”) Bill Wheeler says that diet is “very very central to the revolution. It’s a freeing process which people go through, from living on processed foods and eating gluttonous portions of meat and potatoes, to natural foods and a simple diet that is kinder to your body. A lot has to do with economics. It’s much cheaper to live on grains and vegetables you can grow in your garden. When Gay and I moved here, we had to decide whether to raise animals to slaughter. Gay said she couldn’t do it. Every Thanksgiving, there’s a movement to raise money to buy turkeys, because some people think the holiday isn’t complete without them. But an amazing thing happens when carrion is consumed. People are really greedy, and it’s messy. The stench and the grease stay with us for days.”

Gravy, roast beef, mashed potatoes, Parker House rolls, buttered peas—the weekly fare when Bill was growing up in Bridgeport, Connecticut. His father, a lawyer who speculated famously in real estate, told Bill he could do anything” with his life as long as he got an education. So Bill, self-reliant, introspective, who loved the outdoors, went to Yale and studied painting. After graduating, he came to San Francisco to find a farmhouse where he could work. When he saw the 320-acre ranch which was then a sheep and Christmas tree farm, he felt, “I’ve got to have it. This is my land.” He bought it with his inheritance, and still has enough money to live comfortably the rest of his life. “My parents would be shocked out of their gourds if they saw the land now,” Bill says. “They died before I opened it.”

The idea of open land, or free land, was introduced to Bill by Lou Gottlieb, a singer with the pop folk group, “The Limelighters,” who, in 1962, bought a 32-acre piece of land called Morning Star about ten miles from Wheeler’s Ranch. Gottlieb visits Wheeler’s every Sunday for the feast; when I met him, he was walking barefoot with a pink blanket wrapped around him like a poncho and fastened with a giant safety pin. A man of soaring height with crow eyes and a dark, silky beard, he talks in sermonettes, rising on his toes with enthusiasm. Gottlieb and a friend, Ramon Sender, decided in 1966 to start a community at Morning Star with one governing precept: access to the land would be denied to no one. With no rules, no organization, they felt, hostilities would not arise, and people could be reborn by living in harmony with the earth. Gottlieb deeded the land to God, and, shortly’, a woman sued God because her home had been struck by lightning. “Now that God owns property, “her lawyer argued, “He can be sued for natural disasters.” It was not until 1967, Gottlieb says, that hippies began to patronize open land.

“From the first, the land selected the people. Those who couldn’t work hard didn’t survive. When the land got crowded, people split. The vibrations of the land will always protect the community.” Gottlieb points to the sky. “With open land, He is the casting director.” What happens, I ask, if someone behaves violently or destructively? Gottlieb frowns. “There have been a few cases where we’ve had to ask people to go, but it’s at terrible, terrible cost to everyone’s soul that this is done. When the land begins to throw off people, everyone suffers.” He shakes his body, as if he were the land, rejecting a germ. “Open land has no historical precedent. When you give free land, not free food or money, you pull the carpet out from under the capitalist system. Once a piece of land is freed, ‘no trespassing’ signs pop up all along the adjoining roads.”

Bill Wheeler refers to his ranch as “the land,” and talks about people who live on the land, babies that are born on the land, music played on the land. He “opened the land,” as he phrases it, in the winter of 1967, after Sonoma County officials tried to close Morning Star by bulldozing trees and all the buildings except Gottlieb’s house. Some Morning Star people moved to Wheeler’s, but others traveled to New Mexico, where they founded Morning Star East on a mesa near Taos owned by another wealthy hippie. The Southwest, particularly northern New Mexico and Colorado, has more communes on open land than any other region. The communes there are all crowded, and Taos is becoming a Haight-Ashbury in the desert. More land continues to be opened in New Mexico, as well as in California, Oregon, and Washington. Gottlieb plans to buy land and deed it to God in Holland, Sweden, Mexico, and Spain. “We’re fighting against the territorial imperative,” he says. “The hippies should get the Nobel Prize for creating this simple idea. Why did no one think of it before the hippies? Because hippies don’t work, so they have time to dream up truly creative ideas.”

IT WAS SURPRISING to hear people refer to themselves as “hippies”; I thought the term had been rendered meaningless by overuse. Our culture has absorbed so much of the style of hip—clothes, hair, language, drugs, music—that it has obscured the substance of the movement with which people at Morning Star and Wheeler’s still strongly identify. Being a hippie, to them, means dropping out completely, and finding another way to live, to support oneself physically and spiritually. It does not mean being a company freak, working nine to five in a straight job and roaming the East Village on weekends. It means saying no to competition, no to the work ethic, no to consumption of technology’s products, no to political systems and games. Lou Gottlieb, who was once a Communist party member, says, “The entire Left is a dead end.” The hippie alternative is to turn inward and reach backward for roots, simplicity, and the tribal experience.

In the first bloom of the movement, people flowed into slums where housing would be cheap and many things could be obtained free—food scraps from restaurants, second-hand clothes, free clinics and services. But the slums proved inhospitable. The hippies did nothing to improve the dilapidated neighborhoods, and they were preyed upon by criminals, pushers, and the desperate. In late 1967, they began trekking to rural land where there would be few people and life would be hard. They took up what Ramon Sender calls “voluntary primitivism,” building houses out of mud and trees, planting and harvesting crops by hand, rolling loose tobacco into cigarettes, grinding their own wheat, baking bread, canning vegetables, delivering their own babies, and educating their own children. They gave up electricity, the telephone, running water, gas stoves, even rock music, which, of all things, is supposed to be the cornerstone of hip culture. They started to sing and play their own music—folky and quiet.

Getting close to the earth meant conditioning their bodies to cold, discomfort, and strenuous exercise. At Wheeler’s, people walk twenty miles a day, carrying water and wood, gardening, and visiting each other. Only four-wheel-drive vehicles can cross the ranch, and ultimately Bill wants all cars banned. “We would rather live without machines. And the fact that we have no good roads protects us from tourists. People are car-bound, even police. They would never come in here without their vehicles.” Although it rains a good part of the year, most of the huts do not have stoves and are not waterproof. “Houses shouldn’t be designed to keep out the weather,” Bill says. “We want to get in touch with it.” He installed six chemical toilets on the ranch to comply with county sanitation requirements, but, he says, “I wouldn’t go in one of those toilets if you paid me. It’s very important for us to be able to use the ground, because we are completing a cycle, returning to Mother Earth what she’s given us.” Garbage is also returned to the ground. Food scraps are buried in a compost pile of sawdust and hay until they decompose and mix with the soil. Paper is burned, and metal buried. But not everyone is conscientious; there are piles of trash on various parts of the ranch.

Because of the haphazard sanitation system, the water at Wheeler’s is contaminated, and until people adjust to it, they suffer dysentery, just as tourists do who drink the water in Mexico. There are periodic waves of hepatitis, clap, crabs, scabies, and streptococcic throat infections. No one brushes his teeth more than once a week, and then they often use “organic toothpaste,” made from eggplant cooked in tinfoil. They are experimenting with herbs and Indian healing remedies to become free of manufactured medicinal drugs, but see no contradiction in continuing to swallow any mind-altering chemical they are offered. The delivery of babies on the land has become an important ritual. With friends, children, and animals keeping watch, chanting, and getting collectively stoned, women have given birth to babies they have named Morning Star, Psyche Joy, Covelo Vishnu God, Rainbow Canyon King, and Raspberry Sundown Hummingbird Wheeler.

The childbirth ritual and the weekly feasts are conscious attempts at what is called “retribalization.” But Wheeler’s Ranch, like many hippie settlements, has rejected communal living in favor of a loose community of individuals. People live alone or in monogamous units, cook for themselves, and build their own houses and sometimes gardens. “There should not be a main lodge, because you get too many people trying to live under one roof and it doesn’t work,” Bill says. As a result, there are cliques who eat together, share resources, and rarely mix with others on the ranch. There was one group marriage between two teen-age girls, a forty-year-old man, and two married couples, which ended when one of the husbands saw his wife with another man in the group, pulled a knife, and dragged her off, yelling, “Forget this shit. She belongs to me.”

With couples, the double standard is an unwritten rule: the men can roam but the women must be faithful. There are many more men than women, and when a new girl arrives, she is pounced upon, claimed, and made the subject of wide gossip. Mary Cordelia Stevens, or Corky, a handsome eighteen-year-old from a Chicago suburb, hiked into the ranch one afternoon last October and sat down by the front gate to eat a can of Spam. The first young man who came by invited her to a party where everyone took TCP, a tranquilizer for horses. It was a strange trip—people rolling around the floor of the tipi, moaning, retching, laughing, hallucinating. Corky went home with one guy and stayed with him for three weeks, during which time she was almost constantly stoned. “You sort of have to be stoned to get through the first days here,” she says. “Then you know the trip.” Corky is a strapping, well-proportioned, large-boned girl with a milkmaid’s face and long blond hair. She talks softly, with many giggles: “I love to go around naked. There’s so much sexual energy here, it’s great. Everybody’s turned on to each other’s bodies.” Corky left the ranch to go home for Christmas and to officially drop out of Antioch College; she hitchhiked back, built her own house and chicken coop, learned to plant, do laundry in a tin tub with a washboard, and milk the cows. “I love dealing with things that are simple and direct.”

Bill Wheeler admires Corky for making it on her own, which few of the women do. Bill is torn between his desire to be the benefactor-protector and his intolerance of people who aren’t self-reliant. “I’m contemptuous of people who can’t pull their own weight,” he says. Yet he constantly worries about the welfare of others. He also feels conflict between wanting a tribe, indeed wanting to be chieftain, and wanting privacy. “Open land requires a leap of faith,” he says, “but it’s worth it, because it guarantees there will always be change, and stagnation is death.” Because of the fluidity of the community, it is almost impossible for it to become economically self-sufficient. None of the communes have been able to live entirely off the land. Most are unwilling to go into cash crops or light industry because in an open community with no rules, there are not enough people who can be counted on to work regularly. The women with children receive welfare, some of the men collect unemployment and food stamps, and others get money from home. They spend very little—perhaps $600 a year per person. “We’re not up here to make money,” Bill says, “or to live like country squires.”

When darkness falls, the ranch becomes eerily quiet and mobility stops. No one uses flashlights. Those who have lived there some time can feel their way along the paths by memory. Others stay in their huts, have dinner, go to sleep, and get up with the sun. Around 7:00 P.M., people gather at the barn with bottles for the late milking. During the week, the night milking is the main social event. Corky says, “It’s the only time you know you’re going to see people. Otherwise you could wander around for days and not see anyone.” A girl from Holland and two boys have gathered mussels at a nearby beach during the day, and invite everyone to the tipi to eat them. We sit for some time in silence, watching the mussels steam open in a pot over the grate. A boy with glassy blue eyes whose lids seem weighted down starts to pick out the orange flesh with his dirt-caked hands and drops them in a pan greased with Spry. A mangy cat snaps every third mussel out of the pan. No one stops it…

Nancy, in her shack about a mile from the tipi, is fixing a green stew of onions, cabbage, kale, leeks, and potatoes; she calls to three people who live nearby to come share it. Nancy has a seventeen-year-old, all-American-girl face—straight blond hair and pink cheeks—on a plump, saggy-stomached mother’s body. She has been married twice, gone to graduate school, worked as a social worker and a prostitute, joined the Sexual Freedom League, and taken many overdoses of drugs. Her children have been on more acid trips than most adults at the ranch. “They get very quiet on acid,” she says. “The experience is less staggering for kids than for adults, because acid returns you to the consciousness of childhood.” Nancy says the children have not been sick since they moved to Wheeler’s two years ago. “I can see divine guidance leading us here. This place has been touched by God.” She had a vision of planting trees on the land, and ordered fifty of exotic variety, like strawberry guava, camelia, and loquat. Stirring the green stew, she smiles vacuously. “I feel anticipant of a very happy future.”

With morning comes a hailstorm, and Bill Wheeler must go to court in Santa Rosa for trial on charges of assaulting a policeman when a squad came to the ranch looking for juvenile runaways and Army deserters. Bill, Gay, Gay’s brother Peter, Nancy, Shoshone, and Corky spread out through the courthouse, peeling off mildewed clothes and piling them on benches. Peter, a gigantic, muscular fellow of twenty-three, rips his pants all the way up the back, and, like most people at Wheeler’s, he is not wearing underwear. Gay changes Raspberry’s diapers on the floor of the ladies’ room. Nancy takes off her rain-soaked long Johns and leaves them in one of the stalls.

It is a tedious day. Witnesses give conflicting testimony, but all corroborate that one of the officers struck Wheeler first, leading to a shoving, running, tackling, pot-throwing skirmish which also involved Peter. The defendants spend the night in a motel, going over testimony with their lawyer. Bill and Corky go to a supermarket Lo buy dinner, and wheel down the aisle checking labels for chemicals, opening jars lo lake a taste with the finger, uhmmm, laughing at the “obsolete consciousness” of the place. They buy greens, Roquefort dressing, peanut butter, organic honey, and two Sara Lee cakes. The next morning, Nancy says she couldn’t sleep with the radiator and all the trucks. Gay says, “I had a dream in which I saw death. It was a blond man with no facial hair, and he looked at me with this all-concealing expression.” Bill, outside, staring at the Kodak blue swimming pool: “I. dreamed last, night that Gay and I got separated somehow and I was stuck with Raspberry.” He shudders. “You know, I feel love for other people, but Gay is the only one I want to spend my life with.”

The jury goes out at 3:00 p.m. and deliberates until 9:00. In the courtroom, a mottled group in pioneer clothes, mud-spattered and frizzy-wet, are chanting, “Om.” The jury cannot agree on four counts, and finds Bill and Peter not guilty on three counts. The judge declares a mistrial. The county fathers are not finished, though. They are still attempting to close the access road to Wheeler’s and to get an injunction to raze all buildings on the ranch as health hazards. Bill Wheeler is not worried, nor are his charges, climbing in the jeep and singing; “Any day now…” God will provide.

We must do away with the absolutely specious notion that everybody has to earn a living…We keep inventing jobs because of this false idea that everybody has to be employed at some kind, of drudgery because, according to Malthusian-Darwinian theory, he must justify his right to exist…The true business of people should be to…think about whatever it was they were thinking about before somebody came along and told them they had to earn a living. – R. Buckminster Fuller

HIGHWAY 101 RIBBONING DOWN THE COAST: narcotic pastels, the smell of charbroiled hamburgers cooking, motels with artificial gas-flame fireplaces. Total sensory Muzak. California banks now print their checks in salmon and mauve colors with reproductions of the Golden Gate Bridge, the High Sierras, the Mojave Desert, and other panoramas. “Beautiful money,” they call it. As I cross the San Rafael Bridge, which, because the clouds are low, seems to shoot straight into the sky and disappear, Radio KABL in San Francisco is playing “Shangri-la.”

South of the city in Menlo Park, one of a chain of gracious suburbs languishing in industrial smoke, Stewart Brand created the Whole Earth Catalog, and now presides over the Whole Earth Truck Store and mystique. Brand, a thirty-year-old biologist who was a fringe member of Ken Kesey’s Merry Pranksters, put out the first catalog in 1968 as a mail-order source book for people starting” communes or alternate life-styles. The success of the catalog—it is selling a thousand copies a day—indicates it is answering needs that cut across age and philosophical gaps. One of these is the need to regain control over the environment, so that when the refrigerator breaks, or the electric power goes out, you don’t have to stand, around helplessly waiting for repairmen, middlemen, and technical “experts” to fix things at your expense. The Whole Earth Catalog lists books and tools that: enable one lo build furniture, fix cars, lea in real-estate law, raise bees for honey, publish your own books, build houses out of foam, auto lops, or mud, and even bury your own dead so that the riles of passage are simple and meaningful. The Catalog also speaks to the need to break out of the inflationary cycle of higher earning and higher spending. It offers books such as How to Get Out of the Rat Race and Live on $10 a Month and How to Live on Nothing, and suggests The Moonlighters’ Manual for people who want to earn subsistence money with minimum commitment of psyche.

Brand, says, “I admit we encourage starting from scratch. We don’t say it will be easy, but education comes from making mistakes. Take delivering babies at home. That’s hazardous! We carry books that tell how hazardous it is. People have lost babies that way, but it won’t hit the fan until we lose a few mothers. When it works, though, it’s glorious.” Brand, with oversized blue eyes and gaunt cheeks, breaks into infectious laughter as he describes his fantasies. “The city-country pull is behind everything going on now. An anthropologist Cherokee we know feels the cycle goes like this: a kid grows up, has talent, goes to the city to fulfill himself, becomes an ideologue, his personality deteriorates, and to recuperate, he goes back to the land. The impulse to return to the land and to form “intentional communities,” or communes, is being felt in the sudden demand for publications like The Green Revolution, founded in the 1940s to promote rural revival, and The Modern Utopian, produced by “Alternatives! Foundation” in Sebastopol, California, which also runs a commune matching service.

Brand says there are few real alternative lifestyles right now: “There’s black pride, and the longhaired run for the hills. That’s it. What we want are alternative economies and alternative political systems. Maybe alternative ecologies. You can’t do this with six people.” Brand points out that new social programs “are always parasitic, like newborn babies. They feed off the parent culture until they’re strong enough to be self-sustaining.” The communes in New Mexico, he says, can eventually develop their own economy by trading goods and services and paying in tokens, “like the casinos in Las Vegas. The climate is great for experiments now. There’s no end of resources for promising ideas. But people had better hurry, because the avenues will start being closed off.” He laughs, thrusting his chin up. “Things are getting weirder and weirder.”

No society racing through the turbulence of the next several decades will be able to do without [some] form of future-shock absorber: specialized centers in which the rate of change is artificially depressed…In such slow-paced communities, individuals who needed or wanted a more relaxed, less stimulating existence could find it. – Alvin Toffler, “Coping with Future Shock”

ROADS ACROSS THE UPPER NORTHWEST are flat and ruler-straight, snowbound for long months, turning arid and dusty in the summer. At an empty crossing in a poor, wheat-growing county, the road suddenly dips and winds down to a valley filled with tall pines and primitive log cabins. The community hidden in this natural canyon is Freedom Farm, founded in 1963. It is one of the oldest communes to be started on open land. The residents—about twenty-four adults and almost as many children—are serious, straightforward people who, with calculated bluntness, say they are dropouts, social misfits, unable or unwilling to cope with the world “outside.” The community has no rules, except that no one can be asked to leave. Because it predates the hippie movement, there is an absence of mystical claptrap and jargon like “far out.” Only a few are vegetarians. Members do not want the location of the farm published for fear of being inundated with “psychedelic beggars.”

I drove to the canyon in the morning and, having learned my lesson, left the car at the top and walked down the steep, icy road. The farm is divided into two parts—80 acres at the north end of the canyon and 120 acres at the south. The families live separately, as they do at Wheeler’s, but their homes are more elaborate and solidly built. The first house in the north end is a hexagonal log cabin built by Huw Williams, who started the farm when he was nineteen. Huw is slight, soft-spoken, with a wispy blond beard. His face and voice are expressionless, but when he speaks, he is likely to say something startling, humorous, or indicative of deep feeling. When I arrived, he was cutting out pieces of leather, wearing a green-and-brown lumberman’s shirt and a knife strapped to his waist. His wife, Sylvia, was nursing their youngest son, while their two-year-old, Sennett, wearing nothing but a T-shirt, was playing on the floor with a half-breed Norwegian elkhound. The cabin was snugly warm, but smelled faintly of urine from Sennett peeing repeatedly on the rug. There was a cast-iron stove, tables and benches built from logs, a crib, an old-fashioned cradle, and a large bed raised off the floor for warmth and storage space. On the wall there was a calendar opened to January, although it was March.

I asked Huw how the community had stayed together for seven years. He said, deadpan, “The secret is not to try. We’ve got a lot of rugged individualists here, and everyone is into a different thing. In reflection, it feels good that we survived. A lot of us were from wealthy backgrounds, and the idea of giving it all up and living off the land was a challenge.” Huw grew up on a ranch 40 miles from the canyon. “I had everything. When I was fourteen, I had my own car, a half-dozen cows, and $600 in the bank.” When he was fifteen, his house burned down and he saw his elaborate collections— stamps, models, books—disappear. He vowed not to become attached to possessions after that, and took to sleeping outdoors. He remembers being terrified of violence, and idolized Gandhi, Christ, and Tolstoy. At seventeen, he became a conscientious objector and began to work in draft resistance. While on a peace walk from New Hampshire to Washington, D.C., he decided to drop out of the University of Washington and start a nonviolent training center, a community where people could live by sharing rather than competing. He persuaded his mother to give him 80 acres in the canyon for the project, rented a house, called the Hart House, and advertised in peace papers for people to come and share it with him.

The first summer, more than fifty came and went and they all lived in the Hart House. One of the visitors was Sylvia, a fair-skinned girl with long chestnut hair and warm wistful eyes that hint of sadness. They were married, and Huw stopped talking about a peace center and started studying intentional communities. He decided he wanted a community that would be open to anyone, flexible, with no prescribed rules to live by. Work would get done, Huw felt, because people would want to do it to achieve certain ends. “It’s a Western idea. You inspire people by giving them a goal, making it seem important; then they’ll do anything to get there.” If people did not want to work, Huw felt, forcing them would not be the answer.

The results were chaotic. “Emotional crises, fights over everything. A constant battle to get things done. A typical scene would be for one guy to spend two hours fixing” a meal. He had to make three separate dishes—one for vegetarians, one for non-vegetarians, and one for people who wouldn’t eat government-surplus food. He would put them on the table, everybody would grab, and if you stood back you got nothing. When people live that close together, they become less sensitive, and manners go right out the window. It was educational, but we knew it wasn’t suitable for raising children.” The group pooled resources and bought another 120 acres two miles away. Huw and Sylvia built their own cabin and moved out of the Hart House; another couple followed.

Then around 1966, the drug scene exploded and the farm was swamped with speed freaks, runaways, addicts, and crazies. A schism grew between the permanent people and the transients. The transients thought the permanents were uptight and stingy. The permanents said the transients were abusing the land. When most of the permanents had built their own cabins, they began talking about burning down the Hart House. I heard many versions of the incident. Some say a man, whom I shall call George, burned it. Some say everyone did it. Some said they watched and were against it but felt they should not stop it. Afterwards, most of the transients left, and the farm settled into its present pattern of individual families tending their own gardens, buying their own supplies, and raising their own animals. Each family has at least two vehicles—a car and a tractor, or a motorcycle or truck. Huw says, “We do our share of polluting.”

The majority at Freedom live on welfare, unemployment compensation, and food stamps. A few take part-time jobs picking apples or wheat, one does free-lance writing, and some do crafts. Huw makes about $50 a month on his leather work, Ken Meister makes wall hangings, Rico and Pat sell jewelry to psychedelic shops, and Steve raises rabbits. Huw believes the farm could support itself by growing organic grains and selling them by mail order, but he hasn’t been able to get enough cooperation to do this. “It’s impossible to have both a commune, where everyone lives and works collectively, and free land, where anyone can settle,” he says. “Some day we might have a commune on the land, but not everyone who lived on the land would have to join it.”

The only communal rituals are Thanksgiving at the schoolhouse and the corn dance, held on the first full moon of May. Huw devised the corn dance from a Hopi Indian ceremony, and each year it gets wilder. Huw builds a drum, and at sundown everyone gathers on a hillside with food, wine, the children in costumes, animals, and musical instruments. They take turns beating the drum but must keep it beating until dawn. They roast potatoes, and sometimes a kid, a pig, or a turkey, get stoned, dance, howl, and drop to sleep. “But that’s only once a year,” one of the men says. “We could have one every month, and it would hold the community together.” Not everyone wants this solidarity, however. Some are like hermits and have staked out corners of the canyon where they want to be left alone. The families who live nearby get together for dinners, chores, and baby-sitting. At the north end, the Williamses, the Swansons, and the Goldens pop in and out constantly. On the day I arrive, they are having a garden meeting at the Swansons’ to decide what to order for spring planting.

The Swansons, who have three young children, moved into the canyon this year after buying, for $1,000, the two-story house a man called Steve had built for his own family. Steve had had a falling out with Huw and wanted to move to the south acres. The Swansons needed a place they could move into right away. The house has the best equipment at the farm, with a flush toilet (sectioned off by a blanket hung from the ceiling), running water, and electricity that drives a stove, refrigerator, and freezer. Jack Swanson, an outgoing, ruddy-faced man of thirty-five, with short hair and a moustache, works on a newspaper 150 miles away and commutes to the farm for weekends. His wife, Barbara, twenty-four, is the image of a Midwestern college girl: jeans cut off to Bermuda length, blouses with Peter Pan collars, and a daisy-printed scarf around her short brown hair. But it is quickly apparent that she is a strong-willed nonconformist. “I’ve always been a black sheep,” she says. “I hate supermarkets—everything’s been chemically preserved. You might as well be in a morgue.” Barbara is gifted at baking, pickling, and canning, and wants to raise sheep to weave and dye the wool herself. She and Jack tried living in various cities, then a suburb, then a farm in Idaho, where they found they lacked the skills to make it work. “We were so ill-equipped by society to live off the earth,” Jack says. “We thought about moving to Freedom Farm for three or four years, but when times were good, we put it off.” Last year their third child was born with a lung disease which required months of hospitalization and left them deep in debt. Moving to the farm seemed a way out. “If we had stayed in the suburbs, we found we were spending everything we made, with rent and car payments, and could “never pay off the debts. I had to make more and more just to stay even. The price was too high for what we wanted in life,” Jack says. “Here, because I don’t pay rent and because we can raise food ourselves, I don’t have to make as much money. We get help in farming, and have good company. In two or three months, this house is all mine—no interest, no taxes. Outside it would cost me $20,000 and 8 per cent interest.”

A RAINSTORM HITS at midnight and by morning the snow has washed off the canyon walls, the stream has flooded over, and the roads are slushy mud ruts. Sylvia saddles two horses and we ride down to the south 120. There are seven cabins on the valley floor, and three hidden by trees on the cliff. Outside one of the houses, Steve is feeding his rabbits; the mute, wiggling animals are clustering around the cage doors. Steve breeds the rabbits to sell to a processor and hopes to earn $100 a month from the business. He also kills them to eat. “It’s tough to do,” he says, “but if people are going to eat meat, they should be willing to kill the animal.” While Steve is building his new house, he has moved with his wife and four children into the cabin of a couple I shall call George and Liz Snow. George is a hefty, porcine man of thirty-nine, a drifter who earned a doctorate in statistics, headed an advertising agency, ran guns to Cuba, worked as a civil servant, a mason, a dishwasher, and rode the freights. He can calculate the angles of a geodesic dome and quote Boccaccio and Shakespeare. He has had three wives, and does not want his name known because “there are a lot of people I don’t want to find me.”

Steve, a hard-lived thirty-four, has a past that rivals George’s for tumult: nine years as an Army engineer, AWOL, running a coffee house in El Paso, six months in a Mexican jail on a marijuana charge, working nine-to-five as chief engineer in a fire-alarm factory in New Haven, Connecticut, then cross-country to Spokane. Steve has great dynamism and charm that are both appealing and abrasive. His assertiveness inevitably led to friction in every situation, until, tired of bucking the system, he moved to the farm. “I liked the structure of this community,” he says. “Up there, I can get along with one out of a thousand people. Here I make it with one out of two.” He adds, “We’re in the business of survival while the world goes crazy. It’s good to know how to build a fire, or a waterwheel, because if the world ends, you’re there now.”

Everyone at Freedom seems to share this sense of imminent doomsday. Huw says, “When the country is wiped out, electricity will stop coming through the wires, so you might as well do without it now. I don’t believe you should use any machine you can’t fix yourself.” Steve says, “Technology can’t feed all the world’s people.” Stash, a young man who lives alone at the farm, asks, “Am I going to start starving in twenty years?”

Steve: “Not if you have a plot to garden.”

Stash: “What if the ravaging hordes come through?”

Steve: “Be prepared for the end, or get yourself a gun.”

There is an impulse to dismiss this talk as a projection of people’s sense of their own private doom, except for the fact that the fear is widespread. Stewart Brand writes in the Whole Earth Catalog: “One barometer of people’s social-confidence level is the sales of books on survival. I can report that sales on The Survival Book are booming; it’s one of our fastest moving items.”

Several times a week, Steve, Stash, and Steve’s daughter Laura, fourteen, drive to the small town nearby to buy groceries, visit a friend, and, if the hot water holds out, take showers. They stop at Joe’s Bar for beer and hamburgers—40 cents “with all the trimmings.” Laura, a graceful, quiet girl, walks across the deserted street to buy Mad magazine and look at rock record albums. There are three teenagers at the farm—all girls—and all have tried running away to the city. One was arrested for shoplifting, another was picked up in a crash pad with seven men. Steve says, “We have just as much trouble with our kids as straight, middle-class parents do. I’d like to talk to people in other communities and find out how they handle their teenagers. Maybe we could send ours there.” Stash says, “Or bring teen-age boys here.” The women at the farm have started to joke uneasily that their sons will become uptight businessmen and their daughters will be suburban housewives. The history of Utopian communities in this country has been that the second generation leaves. It is easy to imagine commune-raised children having their first haute-cuisine meal, or sleeping in silk pajamas in a luxury hotel, or taking a jet plane. Are they not bound to be dazzled? Sylvia says, “Our way of life is an over-reaction to something, and our kids will probably overreact to us. It’s absurd. Kids run away from this, and all the runaways from the city come here.”

In theory, the farm is an expanded family, and children can move around and live with different people or build houses of their own. In the summer, they take blankets and sleeping bags up in the cliffs to sleep in a noisy, laughing bunch. When I visited, all the children except one were staying in their parents’ houses. Low-key tension seemed to be running through the community, with Steve and Huw Williams at opposite poles. Steve’s wife, Ann, told me, “We don’t go along with Huw’s philosophy of anarchy. We don’t think it works. You need some authority and discipline in any social situation.” Huw says, “The thing about anarchy is that I’m willing to do a job myself, if I have to, rather than start imposing rules on others. Steve and George want things to be done efficiently with someone giving orders, like the Army.”

At dinner when the sun goes down, Steve’s and George’s house throbs with good will and festivity. The cabin, like most at the farm, is not divided into separate rooms. All nine people – Steve, Ann, and their four children, the Snows and their baby – sleep on the upstairs level, while the downstairs serves as kitchen, dining and living room. “The teen-agers wish there were more privacy,” Steve says, “but for us and the younger children, it feels really close.” Most couples at the farm are untroubled about making love in front of the children. “We don’t make a point of it,” one man says, “but if they happen to see it, and it’s done in love and with good vibrations, they won’t be afraid or embarrassed.”

While Ann and Liz cook hasenpfeffer, Steve’s daughters, Laura and Karen, ten, improvise making gingerbread with vinegar and brown sugar as a substitute for molasses. A blue jay chatters in a cage hung from the ceiling. Geese honk outside, and five dogs chase each other around the room. Steve plays the guitar and sings. The hasenpfeffer is superb. The rabbits have been pickled for two days, cooked in red wine, herbs, and sour cream. There are large bowls of beets, potatoes, jello, and the gingerbread, which tastes perfect, with homemade apple sauce. Afterwards, we all get toothpicks. Liz, an uninhibited, roly-poly girl of twenty-three, is describing bow she hitchhiked to the farm, met George, stayed, and got married. “I like it here,” she says, pursing her lips, “because I can stand nude on my front porch and yell, fuck! Also, I think I like it here because I’m fat, and there aren’t many mirrors around. Clothes don’t matter, and people don’t judge you by your appearance like they do out there.” She adds, “I’ve always been different from others. I think most of the people here are misfits – they have problems in communicating, relating to one another.” Ann says, “Communication is ridiculous. We’ve begun to feel gossip is much better. It gradually gets around to the person it’s about, and that’s okay. Most people here can’t say things to each other’s face.”

I walk home – I’m staying in a vacant cabin – across a field, with the stars standing out in brilliant relief from the black sky. Lights flicker in the cabins sprinkled through the valley. Ken Meister is milking late in the barn. The fire is still going in my cabin; I add two logs, light the kerosene lamps, and climb under the blankets on the high bed. Stream water sweeps by the cabin in low whooshes, the fire sputters. The rhythm of the canyon, after a few days, seems to have entered my body. I fall asleep around ten, wake up at six, and can feel the time even though there are no clocks around. In the morning light, though, I find two dead mice on the floor, and must walk a mile to get water, then build a fire to heat it. It becomes clear why, in a community like this, the sex roles are so well-defined and satisfying. When men actually do heavy physical labor like chopping trees, baling hay, and digging irrigation ditches, it feels fulfilling for the woman to tend the cabin, grind wheat, put up fruit, and sew or knit. Each depends on the other for basic needs – shelter, warmth, food. With no intermediaries, such as supermarkets and banks, there is a direct relationship between work and survival. It is thus possible, according to Huw, for even the most repetitive jobs such as washing dishes or sawing wood to be spiritually rewarding. “Sawing puts my head in a good place,” he says. “It’s like a yogic exercise.”

IN ADDITION TO HIS FARMING and leather work, Huw has assumed the job of teacher for the four children of school age. Huw believes school should be a free, anarchic experience, and that the students should set their own learning programs. Suddenly given this freedom, the children, who were accustomed to public school, said they wanted to play and ride the horses. Huw finally told them they must be at the school house every day for at least one hour. They float in and out, and Huw stays half the day. He walks home for lunch and passes Karen and another girl on the road. Karen taunts him, “Did you see the mess we made at the school?”

“Yes,” Huw says.

“Did you see our note?”

Huw walks on, staring at the ground. “It makes me feel you don’t have much respect for the tools or the school.”

She laughs. “Course we don’t have any respect!”

“Well, it’s your school,” Huw says softly.

Karen shouts, “You said it was your school the other day. You’re an Indian giver.”

Huw: “I never said it was my school. Your parents said that.” Aside to me, he says, “They’re getting better at arguing every day. Still not very good, though.” I tell Huw they seem to enjoy tormenting him. “I know. I’m the only adult around here they can do that to without getting clobbered. It gives them a sense of power. It’s ironic, because I keep saying they’re mature and responsible, and their parents say they need strict authority and discipline. So who do they rebel against? Me. I’m going to call a school meeting tonight. Maybe we can talk some of this out.”

In the afternoon I visit Rico and Pat, whose A-frame house is the most beautiful and imaginative at the farm. It has three levels—a basement, where they work on jewelry and have stored a year’s supply of food; a kitchen-living-room floor; and a high sleeping porch reached by a ladder. The second story is carpeted, with harem-like cushions, furs, and wall hangings. There are low tables, one of which lifts to reveal a sunken white porcelain bathtub with running water heated by the wood stove. Rico, twenty-five, designed the house so efficiently that even in winter, when the temperature drops to 20 below zero, it is warm enough for him to lounge about wearing nothing but a black cape. Pat and Rico have talked about living with six adults in some form of group marriage, but, Pat says, “there’s no one here we could really do it with. The sexual experiments that have gone on have been rather compulsive and desperate. Some of us think jealousy is innate.” Rico says, “I think it’s cultural.” Pat says, “Hopefully our kids will be able to grow up without it. I think the children who are born here will really have a chance to develop freely. The older children who’ve come here recently are too far gone to appreciate the environment.”

In the evening, ten parents and five children show up at the school, a one-room house built with eighteen sides, so that a geodesic dome can be constructed on top. The room has a furnace, bookshelves and work tables, rugs and cushions on the floor. Sylvia is sitting on a stool in the center nursing her son. Two boys in yellow pajamas are running in circles, squealing, “Ba-ba-ba!” Karen is drawing on the blackboard—of all things, a city skyscape. Rico is doing a yoga headstand. Steve and Huw begin arguing about whether the children should have to come to the school every day. Steve says, in a booming voice, “I think the whole canyon should be a learning community, a total educational environment. The kids can learn something from everyone. If you want to teach them, why don’t you come to our house?” Huw, standing with a clipboard against his hip, says, “They have to come here to satisfy the county school superintendent. But it seems futile when they come in and say I’m not qualified to teach them. Where do they get that?”

Steve says, “From me. I don’t think you’re qualified.” Huw: “Well I’m prepared to quit and give you the option of doing something else, or sending them to public school.”

Steve says, “Don’t quit. I know your motives are pure as the driven snow…”

Huw says, “I’m doing it for myself as well, to prove I can do it. But it all fits together.”

They reach an understanding without speaking further.

Steve then says, “I’d like to propose that we go door-to-door in this community and get everyone enthused about the school as a center for adult learning and cultural activity first, and for the kiddies second. Because when you turn on the adults, the kids will follow. The school building needs finishing—the dome should be built this summer. Unless there’s more enthusiasm in this community, I’m not going to contribute a thing. But if we get everybody to boost this, by God I’ll be the first one out to dig.”

Huw says, “You don’t think the people who took the time to come tonight is enough interest? I may be cynical, but I think the only way to get some of the others here would be to have pot and dope.” Steve: “Get them interested in the idea of guest speakers, musicians, from India, all over. We can build bunk dorms to accommodate them.”

Huw: “Okay. I think we should get together every Sunday night to discuss ideas, hash things over. In the meantime, why don’t we buy materials to finish the building?”

On the morning I leave, sunlight washes down the valley from a cloudless sky. Huw, in his green lumberman’s shirt, rides with me to the top road. “My dream is to see this canyon filled with families who live here all the time, with lots of children.” He continues in a lulling rhythm: “We could export some kind of food or product. The school is very important—it should be integrated in the whole community. Children from all over could come to work, learn, and live with different families. I’d like to have doctors here and a clinic where people could be healed naturally. Eventually there should be a ham radio system set up between all the communities in the country, and a blimp, so we could make field trips back and forth. I don’t think one community is enough to meet our needs. We need a world culture.”

Huw stands, with hands on hips, the weight set back on his heels—a small figure against the umber field. “Some day I’m going to inherit six hundred more acres down there, and it’ll all be free. Land should be available for anybody to use like it was with the Indians.” He smiles with the right corner of his mouth. “The Indians could no more understand owning land than they could owning the sky.”

We’ve got to get ourselves back to the garden. – Joni Mitchell, from the song, “Woodstock”

LAST HALLOWEEN IN JEMEZ, NEW MEXICO, the squidlike “rock-drug-alternate-culture” underground gathered itself together to discuss what to do with the energy manifested at Woodstock. How can we use that power, they asked, and prevent it from being sickened and turned as it was at the Rolling Stones Free Concert in Altamont? The answer seemed to generate itself: buy land, throw away the deed, open it to anyone and call it Earth People’s Park. Hold an earth-warming festival and ecological world’s fair—all free. A nonprofit corporation was formed to collect money and handle legal problems. But there would be no authorities and no rules in Earth People’s Park. Paul Krassner, Tom Law, Milan Melvin, Ken Kesey, Mama Cass Elliot, and the Hog Farm traveling communal circus led by Hugh Romney fanned out to sell the idea. They asked everyone who had been at Woodstock in body or spirit to contribute a dollar. At first, they talked of buying 20,000 acres in New Mexico or Colorado. In a few months, they were talking about 400,000 acres in many small pieces, all over the country. They flooded the media with promises of “a way out of the disaster of the cities, a viable alternative.” Hugh Romney, calling himself Wavy Gravy, in an aviator suit, sheepskin vest, and a Donald Duck hat, spoke on television about simplicity, community, and harmony with the land. The cards, letters, and money poured in. Some were hand-printed, with bits of leaves and Stardust in the creases, some were typed on business stationery. One, from a young man in La Grange, Illinois, seemed to touch all the chords:

Hello. Maybe we’re not as alone as I thought. I am 24, my developed skills are as an advertising writer-producer-director. It seems such a waste. I have energy. I can simplify my life and I want to help. I am convinced that a new lifestyle, one which holds something spiritual as sacred, is necessary in this land. People can return to the slow and happy pace of life that they abandoned along with their understanding of brotherhood. Thank you for opening doors.

P.S. – Please let me know what site you purchase so I can leave as soon as possible for it. D